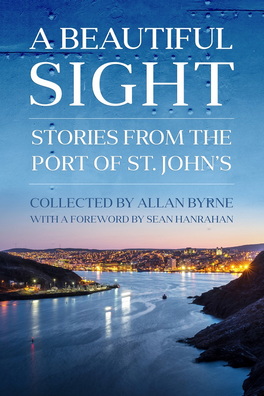

The picturesque Port of St. John’s is an enduring symbol of Newfoundlanders’ inextricable link to the sea. Indeed, it was the geographic features of St. John’s harbour that encouraged initial settlement here, the starting point from which the city expanded. But the legacy of the growth of the port is a unique history unto itself. Playing a major role in the international salt fish trade, the port has been a safe haven for fishermen in the North Atlantic since at least the 1500s, and it later proved a strategic position in WWII during the Battle of the Atlantic. Since then, it has successfully evolved for newer industries and technologies, most notably as a supply base for offshore oilfields as well as the largest containerized cargo handling port in Newfoundland and Labrador. Commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the port’s incorporation under the federal government’s jurisdiction, this book traces the oral history of the port in the twentieth century. Adapted from over a dozen recorded interviews with those who have most intimately seen and shaped the port’s evolution, A Beautiful Sight is a unique glimpse into one of the most storied harbours in North America.

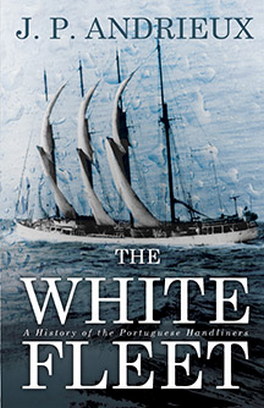

In the fifty years since its incorporation as a federal government port, the Port of St. John’s has undergone remarkable change. Within the past three decades, the port has reinvented itself as a base for the oil industry and a major cargo terminal, a remarkable transformation for a port that credited its existence to the salt fish trade for five centuries. For years the port had hosted the arrival and departure of the spring seal fishery, which brought men from all over the island to the harbourfront in hopes of securing a berth at sea. Fishermen from all over the world relied upon the Port of St. John’s as the only safe haven in the North Atlantic, and many foreign sailors became intimately acquainted with the people and geography of St. John’s. In particular, the annual visit of the Portuguese White Fleet helped strengthen a special cultural relationship that is still nurtured today. For centuries of seamen who worked on these frigid waters, the port was their St. John’s.

Stories collected from:

Robert Innes

David Fox

John Crosbie

Miller Ayre

Captain Sid Hynes

Ches Sweetapple

Glenn Critch

Len Kenny

J. P. Andrieux

Ed Anthony

Albert Burgess

Bill Rompkey

Rob Strong

Excerpt from Ed Anthony

The approach to St. John’s is directly from the North Atlantic, and the direction of the wind really determines how easy your approach to the harbour will be, and how much the seas will co-operate with you. And it is the wind that ultimately controls what you can do and when you can do it. Wind that is blowing from the west or the southwest is blowing outward, so it keeps the sea conditions relatively calm out there. On the other hand, if the wind is from the northeast or the east, there is usually a big swell. You’ll look out through The Narrows and you’ll see the sea breaking up on the side of Fort Amherst and there’s a big wash on. That situation is a very difficult one for some ships because, when you’re making the approach to the harbour, the wind and the sea is astern of the ship. In other words, she’s being skirted along like a sailboat over these waves. It’s even worse if she’s an exceptionally small vessel, because she can be really difficult to keep under control. That’s the worst possible scenario for entering St. John’s harbour.

The narrow channel coming in is fairly unobstructed, although it has been widened. The area you have to enter the channel has been widened by almost a hundred feet. At one time, there was a rock that stood just off the Chain Rock, called Ruby Rock. It only had eighteen feet of water on it, and it posed enough of a hazard so that it was eventually removed. That was done probably in the early 2000s, but it was there during my time as pilot. It wasn’t right in the middle of the channel, so you still had room to go in along past it, and they did it that way for hundreds of years. I actually remember bringing one of the largest vessels ever to come through The Narrows, and I did it with the Ruby Rock still there. It was a big container ship called the Atlantic Cartier. She was brought here because she was discovered to be pumping oil from her bilges en route from Halifax. She was 956 feet – a massive vessel. But anyways, they removed the Ruby Rock and made that depth virtually level with the rest of the channel.

The eventual construction of the Prosser’s Rock Boat Basin changed the landscape of The Narrows even more. It wasn’t yet built when I first started sailing out The Narrows. When it was first proposed, I remember myself and the other pilots sizing it all up, and I remember that we had a somewhat negative impression of it. We figured this was going to make the job a little more difficult and perhaps even a little more dangerous. We envisioned this big structure going right in The Narrows, where we operate. It is a large breakwater that protrudes out perhaps 150 feet, and we figured that it was really going to interfere with our daily work. We envisioned that it was going to create all these different types of currents, and we feared that the sea would heave in and deflect off of it. But I have to admit that it didn’t cause us one bit of trouble in the world. As a matter of fact, I sometimes found it to be an asset more so than anything else. Sometimes when you were entering The Narrows in the thickest of fog and you were passing the lights on the basin’s breakwater, you could at least see a glimmer of light. I’ve come in through there with some pretty big ships sometimes, and you hadn’t been able to see any more than one third of the ship’s length ahead. You’re creeping through this black, pea-soup thickening of fog, and those lights really help guide you in.

People often ask, “How big a ship can come into St. John’s?” Well, physical size isn’t really the question. What really determines a ship’s capability to enter is its displacement underwater, which we refer to as her “draft.” In this case, we always use thirty-six feet (eleven metres) of water as our draft limit in St. John’s. Any vessel that draws more than that, we can’t really bring them in. We don’t run across vessels of this size too often, but I remember navigating a few through that were marginal.

I should say, though, that this is much less of an issue for many of today’s modern vessels. A lot of the ships you see today, while they may not be that big, are highly manoeuvrable – a lot of those supply vessels, for example. They can be controlled meticulously. They’ve got thrusters, two engines, and everything is adjustable. The same applies to many of those newer cruise ships that attract a lot of attention in the harbour. They are massive ships. They don’t have a conventional propeller or a rudder like traditional vessels. Instead, they have a unit that drops down from under the stern, sometimes on either side, and it has the capability to move 360 degrees. You can turn a ship fully around with it. A traditional propeller runs through a ship and is attached firmly to it. Then a rudder sits behind the propeller that directs the flow of water coming from it, causing the ship to change direction. These newer ships use a completely different rudder technology, because they can be turned up to 360 degrees. And if you have two of them on board, that gives you that much more steering ability. Combine this with the fact that many newer ships have so much more horsepower than their older predecessors, and you really get a sense of how powerful and manoeuvrable they are.

Technology has had a major effect on the nature of the harbour pilot’s job. It happened so fast, even within my lifetime. It’s almost fifty years to the day since I started operating ships, and you can’t imagine how much technology has changed my work. It’s almost to the point where they no longer need a guy like me on incoming vessels. What they really need now is a guy who can fix the computer or understand the technology in the event that something malfunctions. You don’t need someone who understands celestial navigation like we used to use. However, they still do need human assistance for the final approach, for that last little bit of maneuvering when you are getting the vessel closely and safely to the dock. I guess that’s what keeps old fellas like me employed!

All the contributors are lively and enlightening.-- The Telegram --

A port that is relied upon as one of the only safe havens in the North Atlantic, its history is as vibrant and captivating as the people of this province.-- Newfoundland Herald --

A Beautiful Sight is an affectionate look at a very important Canadian port that rings true, and deserves a wide audience.-- The Northern Mariner --

[An] engaging collection.-- International Journal of Maritime History --